The festival’s 2020 edition will screen ten feature-lengths and two short film sessions by auteurs like Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, Karel Reisz and Lorenza Mazzetti, all of them representatives of the so-called New British Cinema.

Britain’s Free Cinema will be the subject of a retrospective scheduled as part of the Valladolid Festival’s 65th edition running October 24-31, 2020. This film movement emerged in the 1950s, more specifically in the year 1956, so that it is 65 years now since the first “Angry Young Men’s Manifesto”: an anniversary that coincides with that of the birth of the Valladolid International Film Festival.

Considered a ‘New Cinema’ movement —just like its contemporary counterparts in France (La Nouvelle Vague) or Germany (Neuer Deutscher Film)— the Free Cinema aimed at the renewal of the British film scene by vindicating cinema as an art form and an industry. To this purpose it resorted to a realistic aesthetics and stories inspired by everyday life and committed to the social reality of that time.

Together with writers and playwrights, the Angry Young Men included filmmakers who were against the kind of cinema produced by the big studios and proposed highly different forms of film production which supported low-budget movies whose shooting style was close to that of documentary cinema. Undoubtedly, the distinctive feature of Free Cinema is its particular approach to reality.

The term Free Cinema was coined by a group of young filmmakers (Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, Karel Reisz and Lorenza Mazzetti) when they decided to show their short films at the National Film Theatre in London on February 5, 1956. The first phase of Free Cinema consisted of five programs of short and medium-length films that were gradually released until 1959.

The movement lasted through the 1960s and, although its members became dispersed over time, their ideas never completely disappeared, giving way years later to a new wave of British social realism led by directors such as Ken Loach, Stephen Frears or Mike Leigh, among others.

Two short film sessions and ten feature films

Organized in collaboration with film magazine Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, the retrospective will schedule two of the short film programs presented at the National Film Theatre in London and a dozen feature films.

The first program included a documentary which features an amusement park in Kent, O Dreamland (1953), by Lindsay Anderson; Karel Reisz’s and Tony Richardson’s, Momma Don’t Allow (1956), which follows a group of teenage workers on their evening off, and the art student Lorenza Mazzetti’s Together (1957).

The second program is made up of the short films The Singing Street (1951), by Nigel McIsaac, James T. Ritchie and Raymond Townsend; Wakefield Express (1952) and Every Day Except Christmas (1957), both by Lindsay Anderson ; and Nice Time (1957), by Alain Tanner and Claude Goretta.

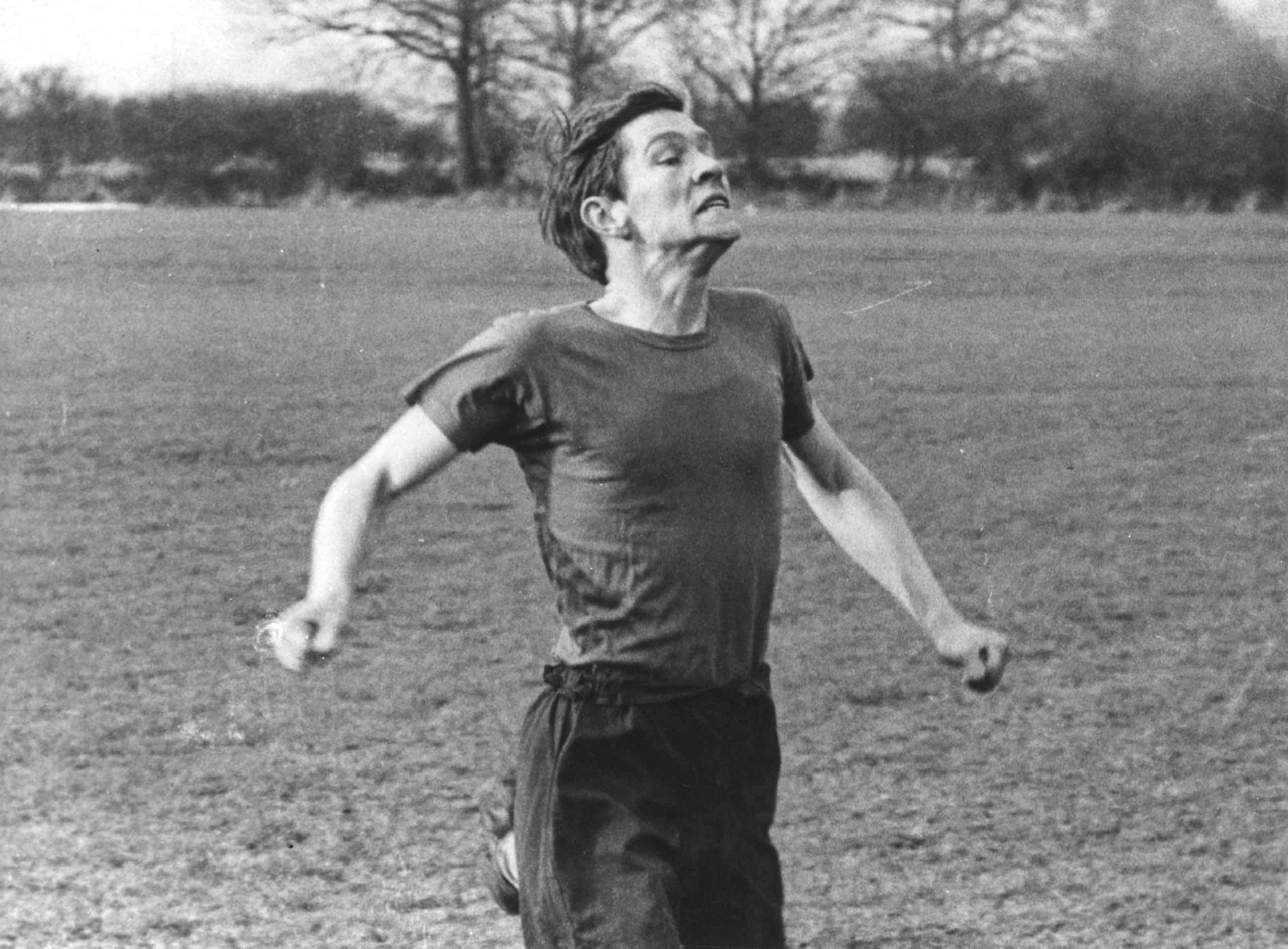

The retrospective will also bring together several feature-length films by the most representative directors of the movement, like Look Back in Anger (1958), based on John Osborne’s play by the same title, which provided the name for the whole of this ensemble of filmmakers ; or The Entertainer (1960), A Taste of Honey (1961) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), all directed by Tony Richardson.

Additional films in this retrospective are Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) by Karel Reisz; A Kind of Loving (1962) and Billy Liar (1963), both by John Schlesinger; The L-Shaped Room (1962) by Bryan Forbes; and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963) —the Gold Spike at the 9th edition of Seminci— and If … (1968).

![Logo Foro Cultural de Austria Madrid[1]](https://www.seminci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Logo-Foro-Cultural-de-Austria-Madrid1-300x76.jpg)