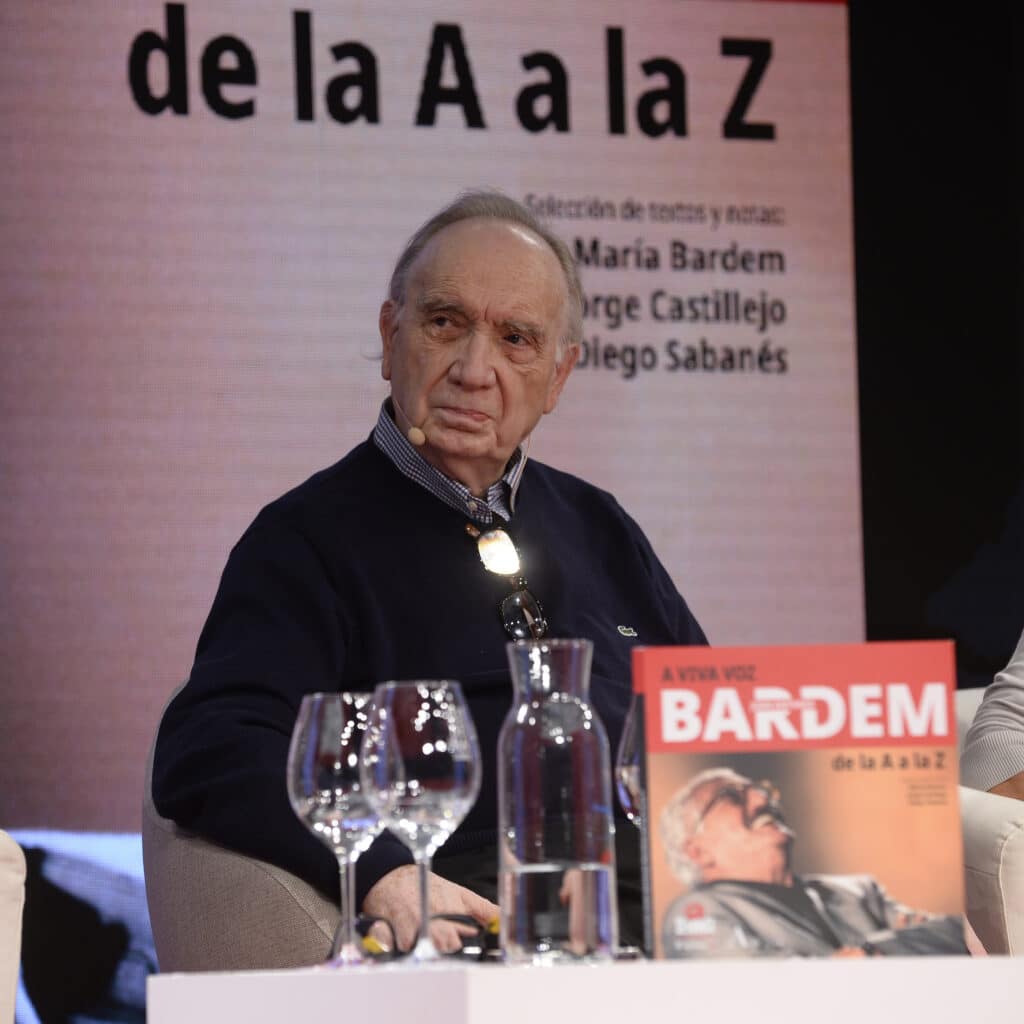

The 67th Seminci presented the book A viva voz. Juan Antonio Bardem, de la A a la Z, with a round table and a colloquium with the participation of family, friends and professionals who worked with the filmmaker

The history of Spanish cinema is written with a B. The centenary of the birth of Luis Buñuel, the most renowned Spanish filmmaker in the world -with the permission of Pedro Almodóvar-, coincided with the turn of the century. Last year it was the turn of Luis García Berlanga, another great among the greats and, in 2022, the anniversary has fallen to Juan Antonio Bardem, to whom the 67th Semana pays tribute with a cycle accompanied by the essay A viva voz. Juan Antonio Bardem, de la A a la Z, which was presented this afternoon at a round table in the Sala Miguel Delibes of the Teatro Calderón moderated by the former director of the Seminci Fernando Lara, who celebrated the existence of this anniversary, “to which other festivals have not granted a margin”, and attended by its authors, María Bardem -daughter of the director-, Jorge Castillejo and Diego Sabanés, accompanied by the president of the Film Academy, Fernando Méndez-Leite, and the editor of the festival’s publications, César Combarros. Also present, in addition to his widow, María Aguado, were his son Juan Bardem and his nephew Carlos Bardem, who later took part in a colloquium at the Teatro Zorrilla together with Manuel Ángel Egea -actor in 7 días de enero (1979)-, María José Alfonso -actress in La huella del crimen: Jarabo (1985)-, Luciano Egido -narrator and essayist responsible for the first monograph on the director: Bardem (1958)-, José Nieto -composer of the soundtrack of El puente (1977)- and Guillermo Maldonado -mountmaster of 7 días de enero- as a prologue to the screening of the RTVE documentary Imprescindibles: Juan Antonio Bardem, vitalista

militante.

“Juan Antonio Bardem is a unique personality in Spanish cinema”, defended Fernando Méndez-Leite, who pointed to the filmmaker’s two masterpieces, Muerte de un ciclista (1955) and Calle Mayor (1956), as “fundamental” in his life’s work. He tackled with courage and with an extraordinary creative and expressive capacity problems of social and political reality that attracted our attention”, explained the president of the Film Academy, who also pointed out that Bardem’s films were truly different from those that populated Spanish screens in those years – a cinema that he defined as “politically ineffective, socially false, intellectually intimate”, socially false, intellectually insignificant, aesthetically null and industrially rickety” during the Salamanca Conversations in 1955 – that “critical gaze”, the result of Bardem’s political commitment, a militant of the PCE, which caused him numerous problems with censorship.

The authors of the book have expressed their satisfaction at the materialisation of a tribute that they had been planning for some time. “I am happy that this dream has come true”, acknowledged María Bardem, who explained how her original idea was to pay tribute to her father with a documentary about the filming of 7 días de enero, which, as a result of the vicissitudes of life, has led to this essay, The filmmaker’s daughter confessed, “We couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things, we couldn’t stop finding things,” she said. “We couldn’t stop finding things, and very valuable things”, explained the scriptwriter and filmmaker Diego Sabanés, for whom the material collected allows us to understand “the evolution of Spanish society, the tastes of the public and the language itself”, as well as Bardem‘s facet as “filmmaker, politician and father”, according to the researcher Jorge Castillejo.

“It is an act of justice that the Seminci has vindicated his legacy”, said the journalist and editor of the festival’s publications, César Combarros, who also reviewed the times the director came to Valladolid, such as when he received the Espiga de Honor in 1987, and his facet beyond directing, as one of the members of the Uninci production company, responsible for a mythical film such as Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961).

The participants discussed the figure of Bardem and his contemporaries, an “impressively fertile and incredibly tenacious” generation, as Sabanés described the filmmakers who began their careers in the 1950s and 1960s, always under the threat of censorship. Filmmakers such as Berlanga, Carlos Saura, Miguel Picazo, Julio Diamante, Mario Camus, Manuel Summers and Basilio Martín Patino, among others, whose films “contained the history of Spain, the history of Francoism”, according to Fernando Lara, referring to filmmakers whose interest was in “reality” and who, he regretted, are not known among young people. “In Bardem’s films we find situations and themes that are completely current”, said Castillejo almost at the end of an event that ended with the filmmaker’s widow in tears and grateful for the tribute. “At times he felt very lonely, it was very difficult for him to get ahead”, said Aguado, who wished that her husband had seen “from above” the affection and devotion of an audience who showed their affection with resounding applause.

“Juan Antonio Bardem was a frustrated artist, a failed man”

After the round table, the colloquium moved to the Teatro Zorrilla, where, before the screening of the RTVE documentary Imprescindibles: Juan Antonio Bardem, vitalista militante, family members and professionals who had worked with Bardem shared their impressions, including that of the author of his first monograph, Luciano G. Egido, novelist, essayist, critic, assistant director and friend of the filmmaker, who, at 94 years of age and displaying an enviable memory that drew applause from the audience, reviewed his career, emphasising both the analysis of what he considers to be his masterpieces and the frustrated experiences he had as a result of his run-ins with the censors.

“He was the critical voice of Spanish cinema at the time. He was a member of the PCE and was faithful to his ideas, which was the great tragedy of his life”, recalled Egido, for whom the filmmaker and friend “sacrificed his professional career for his ideological beliefs”, which, in his opinion, led to a series of “regrettable” films between the mid-sixties and the seventies. “He was a frustrated artist, a failed man”, said the essayist in relation to Bardem’s attempts to make films that did not materialise due to the institutions’ failure to stop them.

Egido praised three of his films, which he considers worthy of standing out in the history of cinema, and praised Bardem’s youth at the time of making them, when he was just over thirty years old. “Cómicos (1954) was a prodigy of technique and was based, above all, on the expressive value of the close-up”, detailed the novelist, who valued the “sensitivity and tenderness” exuded by images inspired by the filmmaker’s childhood and family, a company “that was always condemned to be like the protagonist of his film: someone second-rate”. Regarding Muerte de un ciclista (1955), Egido highlighted “the montage by contrast” that he used to highlight the abyss that separated “the great bourgeoisie of Madrid and the people of the poorest neighbourhoods”, while in Calle Mayor (1956), “an excess of sensitivity”, he emphasised the treatment of its protagonist, Betsy Blair. “Juan Antonio Bardem was finished here”, said Egido, who concluded his speech by recounting how his next film, initially conceived as Los segadores and which ended up being released as La venganza (1958), was massacred by censorship and the impositions of the distribution company, This marked the beginning of the decline of a filmmaker whose political commitment would be resumed in Nunca pasa nada (1963) – which many of the participants considered to be his favourite work- and, after Franco’s death, in works such as El puente (1977) and Siete días de enero (1979), films which Egido considered “interesting, but which no longer had the quality of those of the past”.

![Logo Foro Cultural de Austria Madrid[1]](https://www.seminci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Logo-Foro-Cultural-de-Austria-Madrid1-300x76.jpg)