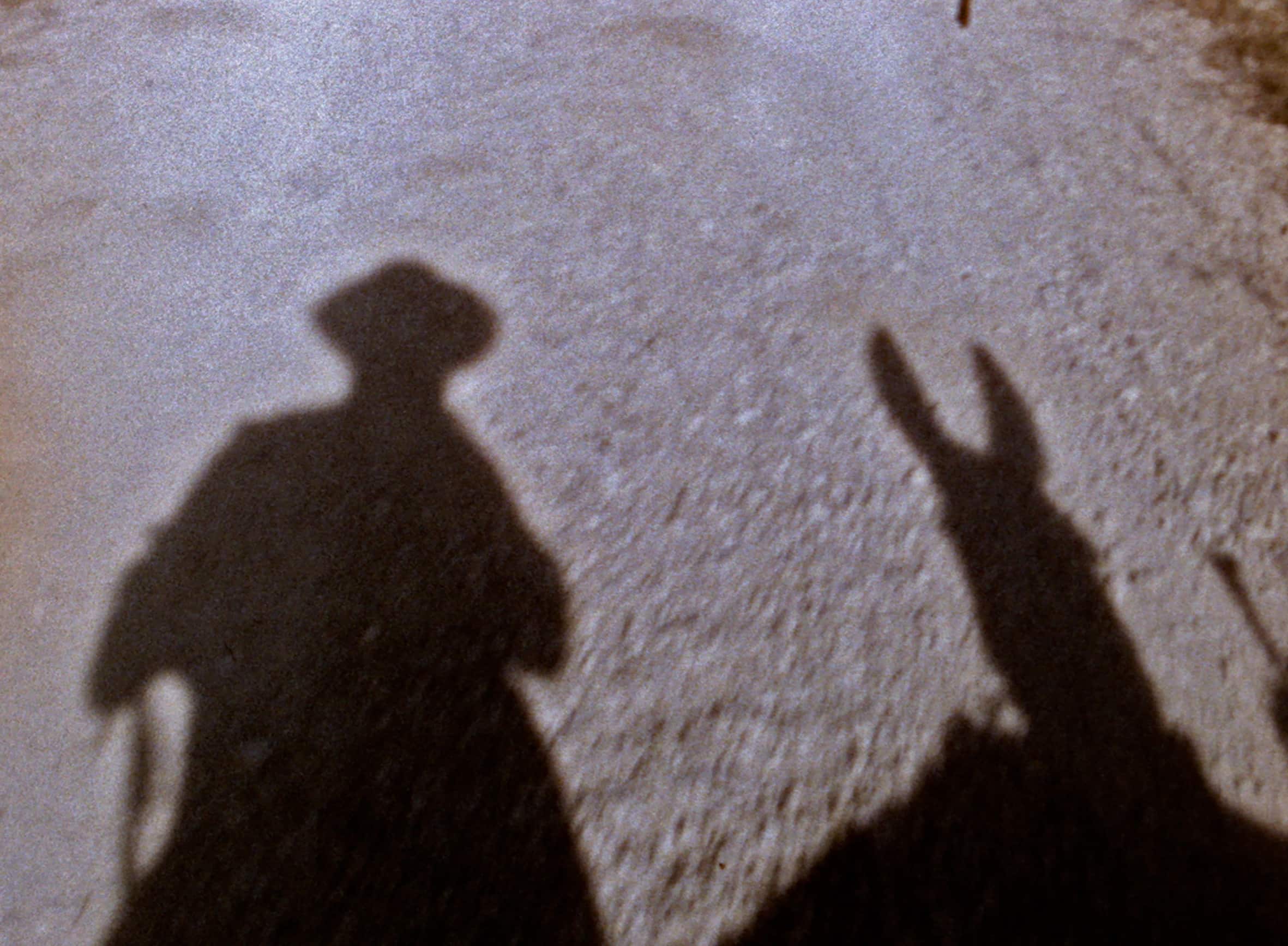

The first question is obligatory and, as Oskar Alegría, the film’s director, has commented: what is Zinzindurrunkarratz? The explanation is not simple: “It is a sonorous toponym”. The filmmaker from Navarre, a journalist by training, who is presenting his feature film in Time of History at the 68th Seminci, has paid tribute to his homeland, his mother, his grandfather, the shepherds of yesteryear and donkeys, all in the same film.

To his land, because he is centered in Navarra. To his mother, because walking through her landscapes helped him in the grieving process after her death. To the shepherds of yesteryear, because they are in danger of extinction. His grandfather, a companaje (the one who brings bread and other food to shepherds who spend six months isolated in the mountains), was one of the 111 who shepherded in the mountains of Navarre when he was active. There is one left,” explained Alegría, “and when he leaves, he will turn off the light”.

It is precisely to the shepherds that we owe these sonorous toponyms, in contrast to the visual toponyms of the type ‘Cerro de los cuatro picos’ (Hill of the four peaks). In the names that interest Oskar Alegria, those that have to do with his tribute, it is the sounds of the countryside that define not only specific places, but entire roads or routes.

Zinzindurrunkarratz is actually a name composed of three names, which define as many sounds. “Zinzin is the sound of a breeze. Durrun is the sound that a stone makes, repeatedly, when falling into a cave; so many ‘durrum’, so many meters the cave has. And karratz is the lightning that always breaks on the same rock. Zinzindurrunkarratz is the name of a path where all this happens”. So that later they say about the German.

A donkey’s superhearing for a film without audio

That leaves the donkey. That animal whose ears are capable of turning almost completely around to perceive even the slightest sound in its environment. And it was fundamental in a filming in which there is only image and the spectator must be the one to add the sound, through his own memories, to the film.

An old super-8 camera is the culprit: “It records video, but not audio”. Using analog support also helped filming in a much more chosen way: “Hitting the record button is 15 euros, so for independent filmmakers it’s important to save money,” he explained.

And here the great help was the donkey itself, which, with the position of its ears, marked the place where the sound to be heard came from or, in other words, the most interesting part of the landscape. “The donkey, when he goes along a road, eats little, but only what is good; the horse gets sick and gets sick. That’s how the donkey eats, that’s how we shot this film.”