After a morning session in which the protagonists set as key the need to digitize and then disseminate, the afternoon session of the day ‘Film Heritage in the 21st Century’ brought together four new professionals out of the 68 that have gathered in Valladolid among the heads of European film libraries and directors of international festivals specializing in the recovery of the film legacy. Once again led by the director of the Filmoteca de Catalunya, Esteve Riambau, the afternoon session was entitled ‘How to program films of the past today: classic film festivals’.

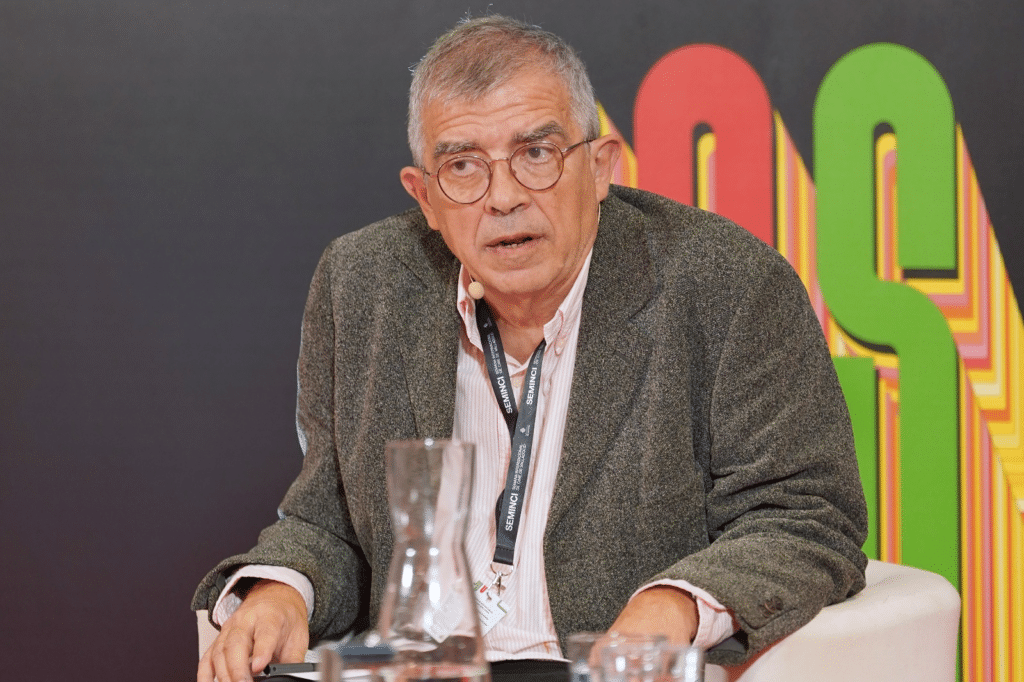

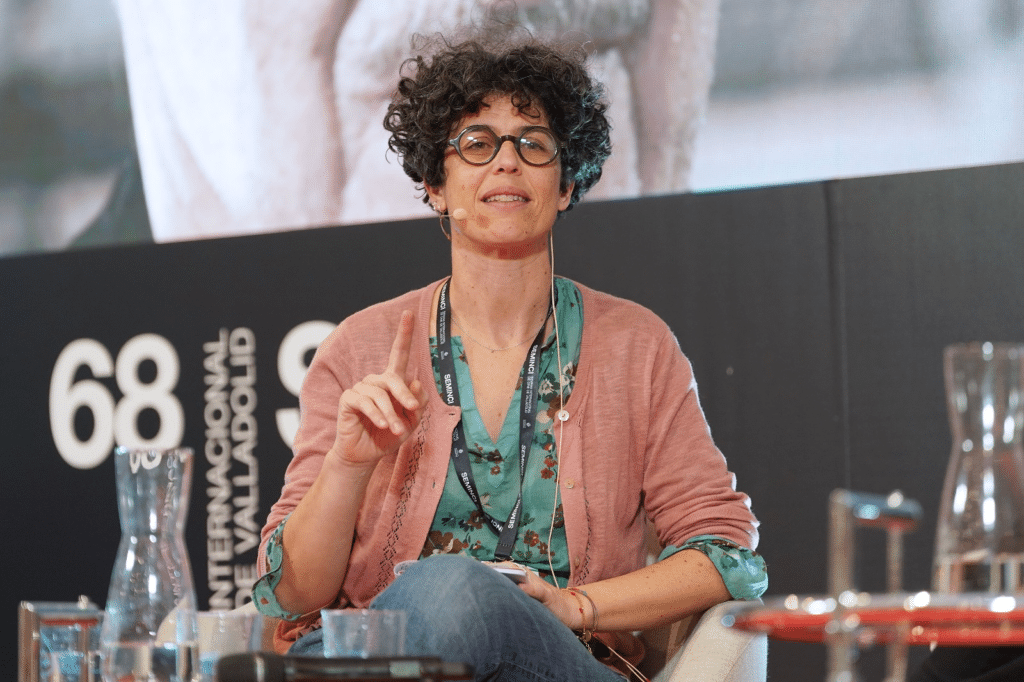

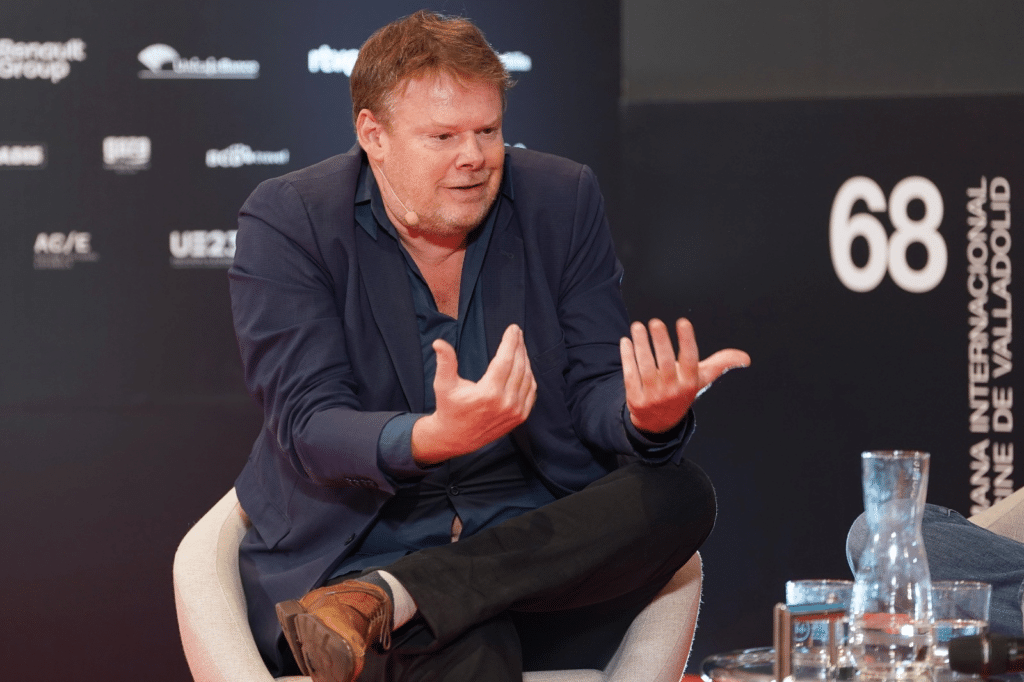

Gerald Duchaussoy, head of Cannes Classics and the Festival Lumière de Lyon; Fréderic Bonnaud, director of the Cinémathèque Française and the Festival Toute la Mémoire du Monde de Paris, spoke on the set of the Calderón Theater’s Hall of Mirrors; Cecilia Cenciarelli, head of the Department of Research and Special Projects at the Cineteca di Bologna and co-director of Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, and Gyorgy Raduli, director of the National Film Institute – Film Archive, Hungary and the Budapest Classics Film Marathon.

Four lovers and scholars of classic cinema, not old, not antique, who agreed that in the beginning it was Bologna, then Lyon, and from there came everything else. That is to say, consensus among the members of the table on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna set the starting point for a complex process that includes the search for small gems, analysis, programming, projection or diffusion, in collusion with film libraries and restorers capable of finding what are sometimes unique copies.

Changing the concept of the misnamed “old cinema”.

For Cecilia Cenciarelli, it is necessary to “change the perspective on the past or the classic”. The why raises, in turn, a host of questions: “They are words that need to be rethought to understand that within them there is a living cinema, sometimes freer, more daring, with many ideas, a lot of imagination, new ideas. We live in a time in which there are many misunderstandings, and we have the possibility of giving access to reflection”.

That reflection comes hand in hand with “programming,” a key word for Fréderic Bonnaud. “One should not think that all the films in the world will always be available to anyone. It’s available if someone programs it,” he said, while acknowledging that the “slightly different” festival of the French Film Library copied Lyon, which in turn copied Bologna.

In the case of Paris, there is always an audience, which allows for greater flexibility in such specialized initiatives. This is not the case in Cannes, as Gerald Duchaussoy explained: “In Cannes we only have an audience during the festival, because it is difficult to stay in Cannes and coming to see Cannes Classique alone is complicated”. Therefore, it functions as a section, not as an independent festival, but without losing sight of an objective more or less common to that of its colleagues: “The purpose when we work on the programming is to have the great works of the history of cinema and that the new public can see them”.

The initiative has grown over the years. While a decade ago it programmed 45 films and two documentaries, last year it screened 200 films and 80 documentaries. In addition to emphasizing restoration, they also choose some rarities: “They are not films that are expected in Cannes and that have many difficulties to find their place in today’s cinema programming and even in a festival like Cannes”.

For Gyorgy Raduli, director, director of the youngest festival at the table, “there are no old films, only films you have already seen”. And the beginnings of the one he leads were in a protest by a group of young people, who asked him to help them make a film to protest the imminent closure of their country’s film archives.

As an alternative to the film, which had all the signs of taking a political turn, or at least of being considered as such, he proposed an international conference of specialists in the field. The repercussion obtained had its political and administrative effect, and the archives remained open. A decade later, in 2017, and after a work of modernization of obsolete documents, that initiative became a festival. “I did a project inspired by Lyon and Bologna. When you have to steal idas, you have to steal from the best.”

Among the points in common, the importance of discoveries to motivate the public, the need to invite protagonists to contextualize and enrich the screenings or the certainty that not everything can be digitized, restored and disseminated. A work that takes place, moreover, in the heart of a changing world in which platforms impose individual consumption versus community enjoyment, but in which festival audiences are open to let themselves be carried away by programmers and watch films they would not look for in other spaces.

“Sometimes a film from many years ago becomes a contemporary film for people in 2023, and that’s wonderful,” said Fréderic Bonnaud.

![Logo Foro Cultural de Austria Madrid[1]](https://www.seminci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Logo-Foro-Cultural-de-Austria-Madrid1-300x76.jpg)