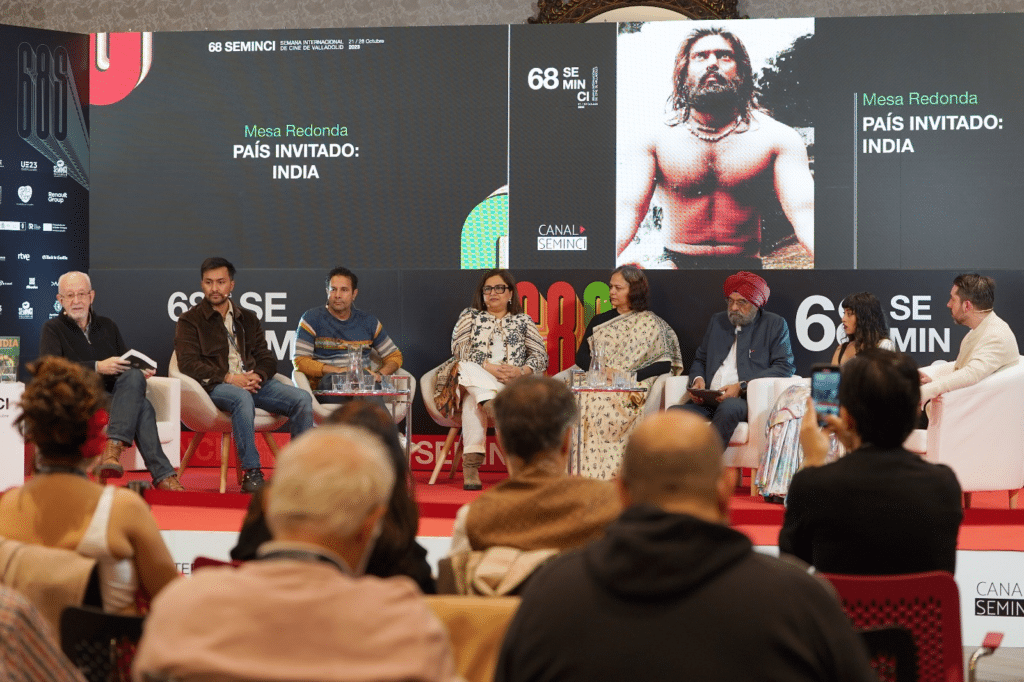

India, as guest country, presented a double challenge for the Valladolid International Film Festival: “To approach one of the most interesting cinematographies for the festival and to do it with height”. This was explained by Javier Estrada, programmer of the 68th edition of the Seminci and moderator of the round table ‘The cinema of India: traditions, ruptures and dissidences‘.

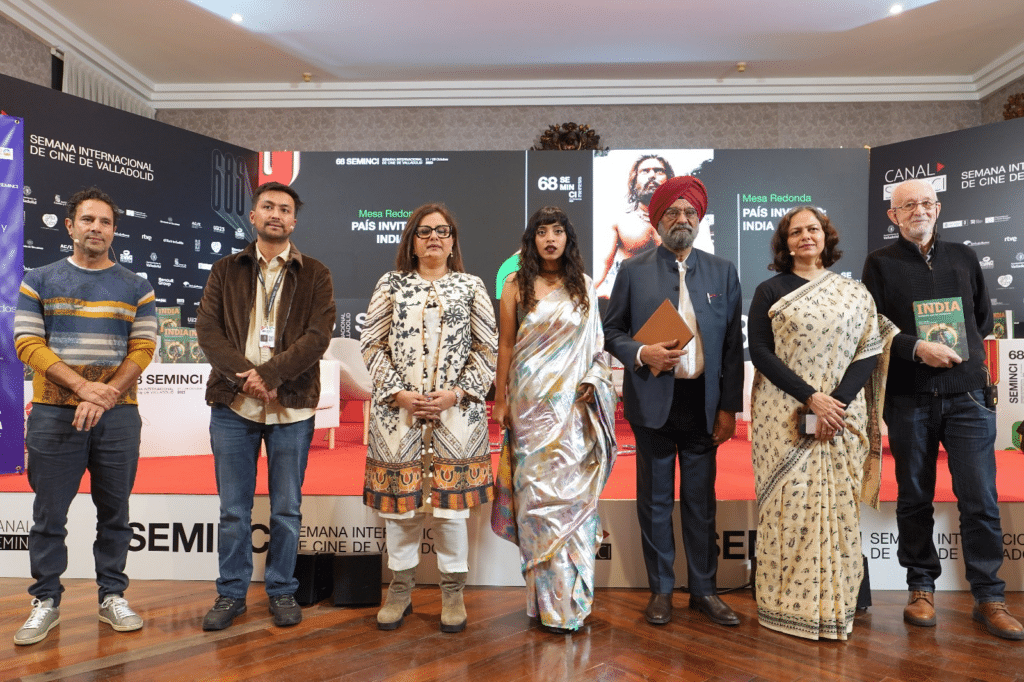

The historian and critic Carlos Heredero, editorial director of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, participated in the event, which borrowed its title from the book that was also presented at the same event; filmmakers Stenzin Tankong (Last Days of Summer), Tarsem Singh (Dear Jassi) and Reema Sengupta/Reema Maya (Nocturnal Burger); actress, producer and social activist Vani Tripathi; Nerja Shekhar, additional secretary of the National Film Development Corporation Nfdc India, and Indian filmmaker and producer Bobby Bedi.

Although the relationship between the festival and India is a long-standing one, as Nerja Shekhar pointed out, “this edition is the culmination of that collaboration,” which includes a retrospective, the Flamenco India exhibition, the publication of the book and the round table itself. As a starting concept, “the dialogue between key works in the history of India with contemporary works,” as explained Estrada.

Quality narratives and entertainment

The guests at the table have developed an interesting debate on the history and the present moment of Indian cinema. Bobby Bedi has chosen as a starting point for his vision the volume that has been presented: “The book that Heredero coordinates also speaks of our history. The moment musical cinema came along, we moved that way and it was used not to continue the story, but to interrupt the story. It is the moment when we were exposed to youth cinema and from then on everything has been a roller coaster, in which there is commercial and independent cinema. High quality narratives and space for music and entertainment for the masses”.

A similar but thematically focused view was expressed by Vani Tripathi: “I would never disagree with a mentor like Bobby, but I think there is only good cinema and bad cinema, and in India we make both. What has changed in today’s narratives is that we have started looking in the mirror and we are not afraid of very close contexts in our lives, even of extreme realities in our communities, our society and the people who inhabit them.”

For the actress and producer, “narrative does not depend only on the power of magic, but on the power of realism“. At festivals like the Seminci, she said, people don’t talk about whether the films are good or bad, but about the impact they generate when they are seen. And he has stopped at the turn towards the female world: “There is an explosion that also includes the gaze of women. In previous narratives, if the gaze was female or the protagonist was female, the film would often not be able to sell in the market, and that has changed. We are getting rid of a certain burden from the past. There are more and more stories about real people,” he said.

Digitization of the world and hybridization

The democratization imposed by digital disruption is a possible cause of this new way of contemplating more intimate spaces. For Stentin Tankong, productions have changed since he was a child, and he has no difficulty in jumping on board: “When I was growing up, the only cinema available to me was Bollywood. Later I have learned more about cinema from other regions, and I connect more with those regional cinematographies.”

The filmmaker gave as an example those of the Himalayas, an environment in which there are very vast regions with very few people. “Now there is a new generation that I try to draw inspiration from, and not make Hindi films, but films focused on our own history, which is huge and there are many things to tell.”

Reema Sengupta also looks at cinema from this perspective. For the director, India has a very long history of independent and commercial cinema and “on the part of independent cinema there is an interesting reflection, but also an “escapist” side of commercial cinema”. For her, versatility is fundamental, exploring new narrative techniques and taking advantage of a moment in which the democratization of the medium thanks to the digital revolution allows access to audiovisual products to people who previously did not have it. In addition, she said, “now there are many young people who show solidarity and cooperate with each other”. The peculiarities of Indian cinema and the possibilities of collaboration with European cinema or the narrative conditioning factors of these peculiarities were in the spotlight of the speakers. It was Nerja Shekhar who perfectly summarized the different points of view between possible intersections between East and West, and expanded to new open doors, if possible: “We have many similarities, a lot of diversity and a lot of respect for diversity. In addition to film, there is a growing sector, animation, where there is a growing collaboration. So I predict a very bright future”.

![Logo Foro Cultural de Austria Madrid[1]](https://www.seminci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Logo-Foro-Cultural-de-Austria-Madrid1-300x76.jpg)