- In connection with this year’s section dedicated to Germany as guest country, filmmakers Helena Wittmann and Thomas Arslan have talked to Carlos Losilla, coordinator of the book ‘ Mirror of Passions’, about the past, present and future of German cinema.

Valladolid, 25 October 2024. The 69th edition of the Valladolid International Film Festival has dedicated, for the first time in the history of the festival, an exhaustive retrospective to German cinema. Following the innovative structure that Destival proposed in the previous edition for the national retrospectives, past and present dialogue through films belonging to the New German Cinema (with works by Wim Wenders, Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, but also lesser-known but equally stimulating female authors such as Elfi Mikesch, Helma Sanders-Brahms and Sohrab Shahid Saless), and titles from the last twenty years, including icons of the Berlin School such as Ghost (Christian Petzold), Western (Valeska Grisebach) and The Forest for the Trees (Maren Ade). A bridge between modernity and contemporaneity that focuses on the most audacious voices of German cinema, with emotional warmth and humanism as communicating vessels between all the selected works.

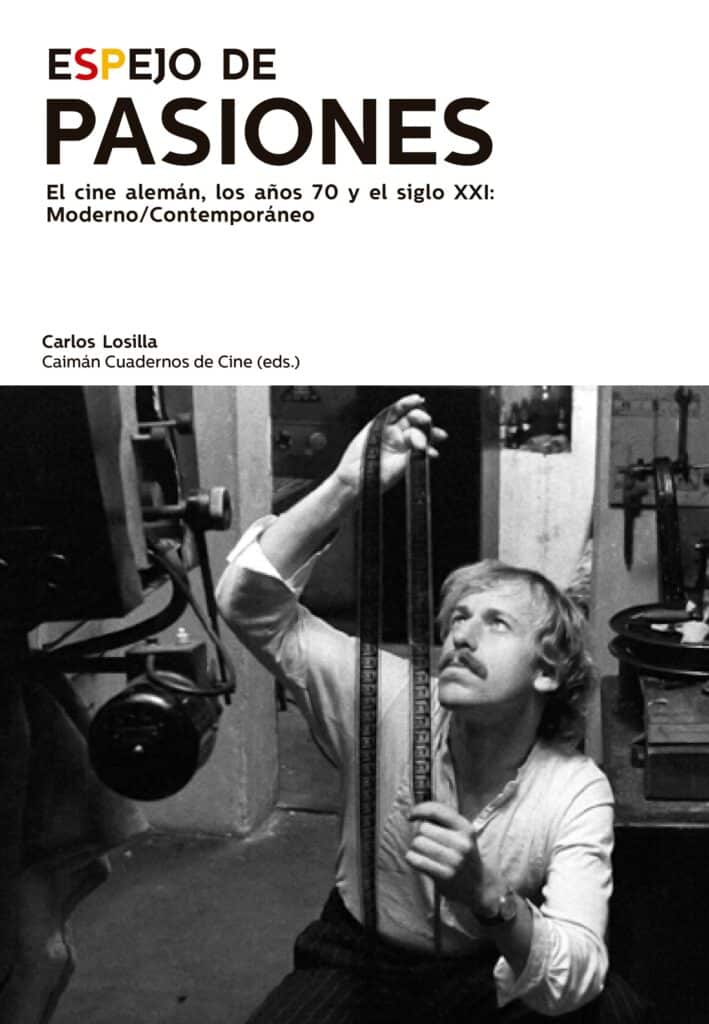

In the same spirit, and in collaboration with the magazine Caimán Cuadernos de Cine, the festival has published the book Mirror of Passions. German Cinema, the 1970s and the 21st Century: Modern/Contemporary, coordinated by Carlos Losilla. In the words of the critic: ‘Our intention was not to be exhaustive, nor did we envisage the publication as an encyclopaedia of German cinema. What we were looking for was to establish the idea of a mirror, which also dominates the cycle, between this almost end of the century and the beginning of a new one’. And he added: ‘The result is a puzzle, and that is where you as readers come in, to finish composing it and fill in the holes based on what you already know about the subject and also on what you have been able to see in the cycle. It is an invitation to get to know this vast constellation of authors, authors, films, modes and styles’.

The presentation of the book is part of the cycle of round tables ‘Thinking about cinema’, a space in which the filmmakers Helena Wittmann, member of the Alquimias Jury, and Thomas Arslan, who is participating in Meeting Point with his most recent film, Scorched Earth (2024), have talked. The filmmakers have addressed some of the themes that have united and motivated German auteurs, both in the past and in the present, such as the search for freedom.

Emotional Landscapes. Passions in German cinema

‘In the 80s and 90s, when I started filmmaking, there was a very narrow idea of German cinema. For me it was always more stimulating to look at what had been made decades before. And I was driven by an impulse to look for something different, to get out of the clichés and to come to a real vision of what cinema was. I felt that the points of view had to be broader,’ said Arslan.

Wittmann also shared his experience: ‘It was similar for me, although I started much later. There was always the idea of seeking change, of mobilising and criticising structures. It wasn’t easy, because there was still a kind of ghost of the people who used to dictate what cinema had to be in Germany. But my generation wanted to do different things. And right now it’s a bit like that too’.

In addition, the two have emphasised the current difficulties of the German film industry. ‘The conditions are not the best, there is less and less support and opportunities. These are things we have to change,’ said Arslan. Wittmann added: ‘We love what we do. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be able to make our films.

As Javier H. Estrada, head of programming at SEMINCI and moderator of the roundtable, pointed out, another great motivation of German cinema has always been the portrayal of the other, driven by the need to go beyond national borders. In Arslan’s case, this had to do with his own roots: ‘My father was Turkish and my mother German, so I have experienced the clash of cultures firsthand. And it was important to me that this reality should be reflected in German cinema.

The filmmaker has also expanded on the trilogy he began in 1999 with Dealer, which follows a migrant character he returns to in Scorched Earth: ‘I wanted to fight against the lack of representation I saw in German cinema and show what these young people who came from elsewhere were like and how they lived in Berlin in the 1990s, which, of course, is not the same city as it is today. I thought it was interesting to show these changes. Always with a global vision, which is also something inherited from the cinema of the 70s.

Wittmann’s films, for their part, are eminently transnational in nature, seeking to transcend place through the idea of the journey. In this respect, the director has pointed out: ‘For me, it’s not idealistic. It came about organically. I was born in Germany and there were parts of my family that didn’t have a concern for the other. But I have always found myself on that kind of border between the national and the corporeal’.

This idea of otherness has also been one of the driving forces behind the book co-published by SEMINCI and Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. As the coordinator pointed out: ‘We approach the book as foreigners too; we are just locals talking about German cinema. And this is very interesting because it allows us to see how cultures are connected. The authors of this book have been able to see this and to dialogue with a culture that seems distant, but deep down it is not’.

Press contact:

983 42 64 60

prensa@seminci.com

![Logo Foro Cultural de Austria Madrid[1]](https://www.seminci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Logo-Foro-Cultural-de-Austria-Madrid1-300x76.jpg)